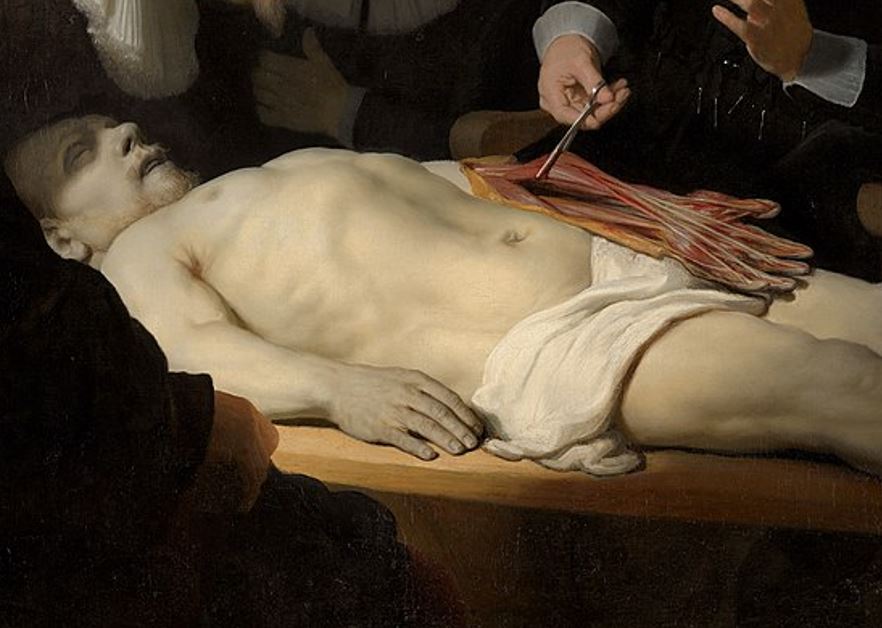

About two and a half centuries before Thomas Eakins painted his world-famous “The Gross Clinic” (1875) a Dutch artist produced a similar frightening painting.

The main difference, however, is that his work depicts the anatomy of a corpse, not an injured human being who was being operated on.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) was one of the most versatile artists in history and he produced one of his ultimate masterpieces at the start of his career in Amsterdam.

In this article, you’ll discover some of the most interesting facts about The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, a fascinating painting by Rembrandt for multiple reasons.

1. It was completed shortly after he set up his studio in Amsterdam

Rembrandt van Rijn was born and raised in Leiden, a city in the province of South Holland in the western part of the country.

He studied at the University of Leiden where his incredible talent for painting was noted. He started his apprenticeship in his native city and also spent 6 months in Amsterdam during his teenage years.

He set up his studio in Leiden in the mid-1620s and became the most successful painter in the city.

Amsterdam was already becoming the cultural and economic center of the Dutch Republic at the time and he moved there in 1631.

Rembrandt completed The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp in 1632 and it’s considered to be his first major commission after moving to Amsterdam as a young 25-year-old artist.

2. It depicts an anatomy lesson from the Amsterdam Guild of Surgeons

The depicted event took place on January 31, 1632. It was the yearly public dissection of the Guild of Surgeons in Amsterdam.

Nicolaes Tulp (1593-1674) is the man performing this dissection of a corpse and he was the official city anatomist.

He is surrounded by doctors who either stare at the viewer or carefully watch what Dr. Tulp is doing as he cuts open the arm of the deceased man.

Just like in Eakins’s masterpiece The Gross Clinic, this event took palce in a theater-like room where dozens of people gathered and looked as if they were watching a theater performance.

The stylish contemporary clothes the men wear emphasize the importance of this 17th-century social event.

3. Rembrandt’s work is not an accurate depiction of this event

Although this event took place a the end of January in the year 1632, Rembrandt took a number of liberties when painting this work.

The two most noteworthy unrealistic elements are:

- The cutting wouldn’t have been done by Nicolaes Tulp himself but by a man who was in charge of preparing the body. Rembrandt left this “Preparer” out of the painting.

- Dutch researchers conducted an experiment with a male cadaver in 2006 and revealed that the exposed left forearm doesn’t look quite the same as in Rembrandt’s painting.

4. The doctors paid to be included and some were added to the painting later

Because of the inaccurate depiction of the event, we have to see this painting as a portrait of the doctors who attended the anatomy lesson.

This means that Rembrandt earned a good amount of money for this work since all of them paid the artist to be included.

This work was radically different than the paintings that had been commissioned earlier. It was such a success that several paid to be included after it was completed.

The men on the left and the uppermost standing man were added shortly after the painting was completed.

5. The corpse was that of a known criminal who was executed on the same day

The dead man on who the anatomy lesson was conducted didn’t volunteer for this, nor did he give his consent for this experiment to take place.

His name was Aris Kindt, also known as “Adriaan Adriaanszoon,” a notorious criminal in the Dutch Republic in the early 17th century

As a result of a crime spree that included armed robbery, he was sentenced to death by hanging and executed on the same day that The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp took place.

6. It was not the only anatomy lesson that the artist painted in his career

Rembrandt continued to earn prestigious commissions throughout his career, something that makes it all the more remarkable that he struggled with financial problems at the end of his life.

The successor of Dr. Niolaes Tulp was a man named Dr. Jan Deijman (1619–1666) and the Surgeons Guild of Amsterdam commissioned a very similar painting from Rembrandt in 1656.

Unfortunately, most of this work was destroyed during a fire in 1723, and only a fragment of the actual brain surgery in The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Deijman remains today.

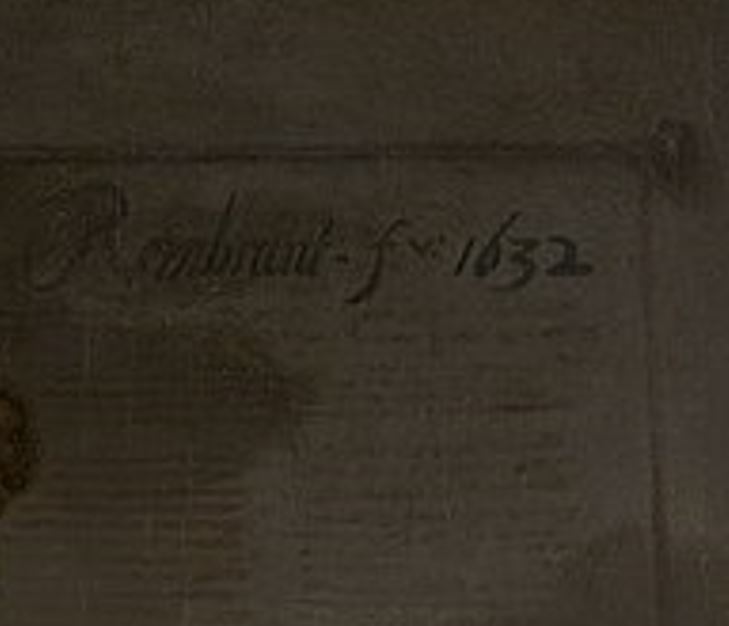

7. Rembrandt’s signature emphasizes his confidence as an artist

The artist added his signature “Rembrandt. f[ecit] 1632” at the top of the work and it was probably the first time he used his first name.

Before this painting, he simply used his initials “RHL” which meant “Rembrandt Harmenszoon of Leiden.”

His first major commission surely gave him a confidence boost because he only used this particular signature throughout his career starting in 1633.

Upon closer inspection, you can see that the navel of the criminal’s corpse has a strange shape. It almost looks as if it depicts the letter “R.”

It’s possible that this was a variation of Rembrandt’s signature which he experimented with at the time. He finally settled for using his first name in 1633.

9. How big is The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp by Rembrandt?

The doctors paid Rembrandt handsomely and he rewarded them with a large painting that highlights the importance of their annual anatomy lesson.

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp is a large oil on canvas painting that has dimensions of 216.5 × 169.5 centimeters (85.2 × 66.7 inches).

10. Where is Rembrandt’s fascinating painting located today?

The Amsterdam Guild of Surgeons was headquartered in a 15th-century building in Amsterdam called “The Waag.” This had originally been a city gate that was part of the medieval walls of Amsterdam.

The second floor of this so-called “Weigh House” was used by the Guild as their meeting place in the 17th century and the painting hung here for many centuries.

The painting didn’t stay in Amsterdam as it was purchased by the Dutch State in 1798 and moved to The Hague in 1828 on the order of King William I.

Today, you can still admire Rembrandt’s masterpiece in this Dutch city as it’s part of the collection of the Mauritshuis. This museum houses some of the ultimate Dutch Golden Age masterpieces