Very few paintings in the oeuvre of J.M.W. Turner define the artist’s career as this remarkable masterpiece of the Romantic era.

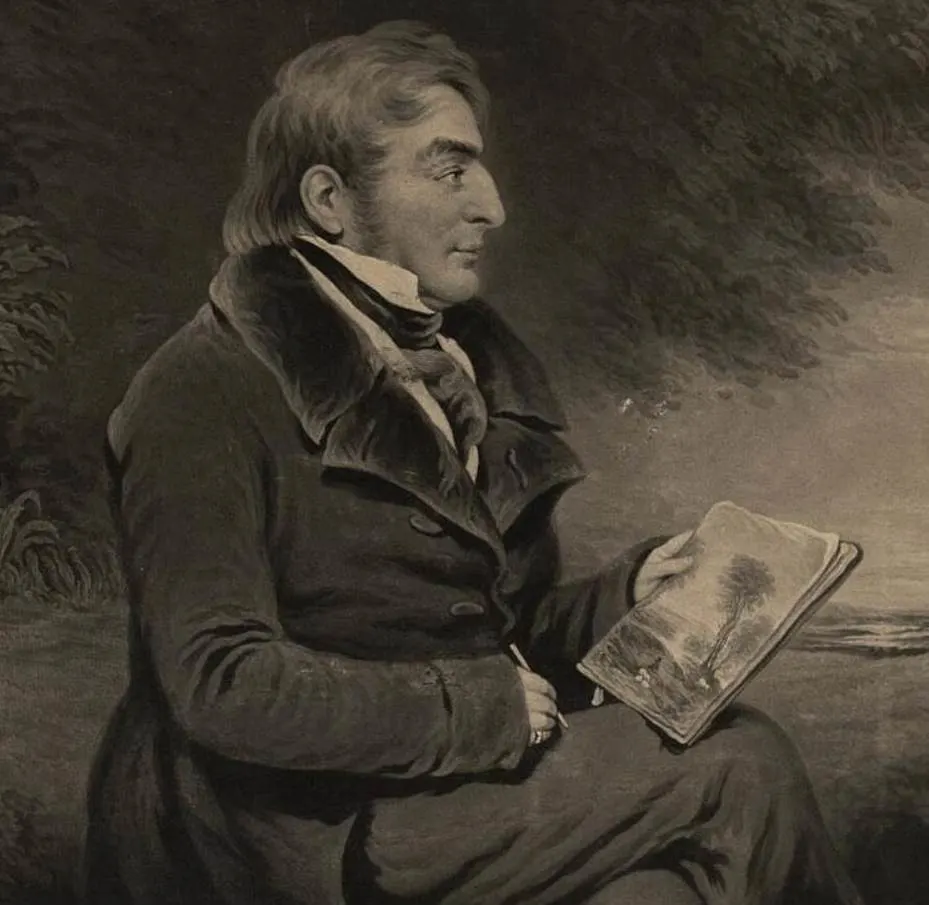

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851) was an English artist who defined the world of art. He managed to convey a special atmosphere into his works which made him stand out from other Romantic artists at the time.

In this article, we’ll take a closer look at some of the most interesting facts about Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway by J.M.W. Turner, one of his most fascinating paintings.

1. It was probably completed in the early 1840s

J.M.W. Turner was one of the leading artists of the Romantic era in the first half of the 19th century. His career already started in 1789 when he started studying at the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

He was barely 14 years old at the time, a testimony to the talent that the young artist showed during his teenage years.

He was born and raised in London, and although he traveled frequently, he continued to live in London for the rest of his life.

His extremely colorful, yet hazy paintings were in high demand. He was a bit of an eccentric because he lived in squalor during the final decades of his wife, leaving behind a small fortune when he passed away in 1851.

Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in the year 1844, although it might have been painted a few years earlier.

2. The painting depicts a train from a former British railway company

As the name of the painting suggests, it depicts an oncoming training of the Great Western Railway (GWR). This was a former British railway company that started operations in 1835.

It was privately owned and as its railway lines expanded, connected London to the southwest and west of England, as well as the West Midlands and Wales.

Most of the privately-owned railway companies were nationalized through the Railways Act of 1921, but it took until 1947 before this particular company became the Western Region of British Railways.

The painting depicts a new means f transport that emerged at the end of the Industrial Revolution. Turner was one of the few artists who painted trains during the early phase of their existence.

3. It depicts a railway bridge that was completed a few years earlier

Numerous railway bridges were constructed during these decades to expand the network of railway lines all across the United Kingdom.

Although it’s very hard to determine due to the extremely hazy landscape, art historians accept that Rain, Steam and Speed depicts the Maidenhead Railway Bridge just west of London.

Just like the railway lines themselves, the bridge was designed by English engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859), arguably the most important engineer in England of the 19th century.

This arch bridge was constructed using bricks and was completed in 1839. This was around the time that the first trains in England started running so it was a pioneering building.

4. An element in the bottom left corner confirms it’s crossing a river

The longer Turner’s career lasted, the hazier his paintings became. Since this work was completed during the final decade of his life, it’s a perfect example of Turner’s style during this period.

This also means that many elements in his colorful works are hard to distinguish. It’s virtually impossible to see that this train is actually crossing a river.

The atmospheric waterbed of the river can be seen in one particular area of the painting in the bottom left corner. Here, Turner painted a man peddling around in the river in a small boat.

5. Turner masterly integrated a sense of motion into this painting

The train appears to be escaping a violent thunderstorm in the distance. It emerges out of the hazy background of the painting as a dark colossal symbol of the Industrial Revolution.

The bridge was much narrower at the time than it is today because it was significantly widened during the 1890s. Today, it’s able to carry 4 standard-gauge tracks.

The most interesting element in this painting is the one feature that set J.M.W. Turner apart from all his colleagues. He managed to integrate a sense of motion into this work.

3 puffs are released from the train’s engine. The first one is clearly visible, while the others fade into the distance. This makes it appear as if the train is really moving toward the viewer at high speed.

Although the average speed of such a train in the 1840s was merely 53 kilometers per hour (33 mph), it could reach speeds of 96 kilometers per hour (60 mph) on long stretches.

6. The train speeding towards the viewer has a deeper meaning

The train we can see in this painting was of the so-called GWR Firefly Class. It was first introduced between 1840 and 1842 which was around the time this painting was completed.

It became outdated a couple of decades later and was gradually withdrawn from the railway lines between December 1863 and July 1879.

Regardless of this fact, depicting this train had a deeper meaning for Turner. He wanted to capture the emerging new technology just like he did with a variety of other inventions of the Industrial Revolution.

Some art historians suggest that the emerging train, which appears to be coming out of nowhere, is a metaphor for the Industrial Revolution, and more specifically, the emergence of a new age.

In that sense, the deeper meaning of this painting can be compared to that of “The Fighting Temeraire,” a painting that depicts an old warship being towed towards its final berth.

7. How big is Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway by J.M.W. Turner?

Turer was an extremely prolific artist who produced over 550 oil paintings, over 2,000 watercolors, and an incredible 30,000 works on paper. While most of his paintings aren’t huge, they aren’t exactly small either.

Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway by J.M.W. Turner is an oil on canvas painting that has dimensions of 91 × 121.8 centimeters (36 × 48 inches).

8. Where is the painting located today?

This particular work was one of the paintings that was still in the artist’s possession when he passed away and which became part of the legal battle that ensued in the following years.

It was finally bequeathed as part of the “Turner Bequest” in 1856 and became part of the collection of the National Gallery in London.

Today, you can still admire the painting in one of the most popular museums in the United Kingdom in the heart of the City of Westminster.