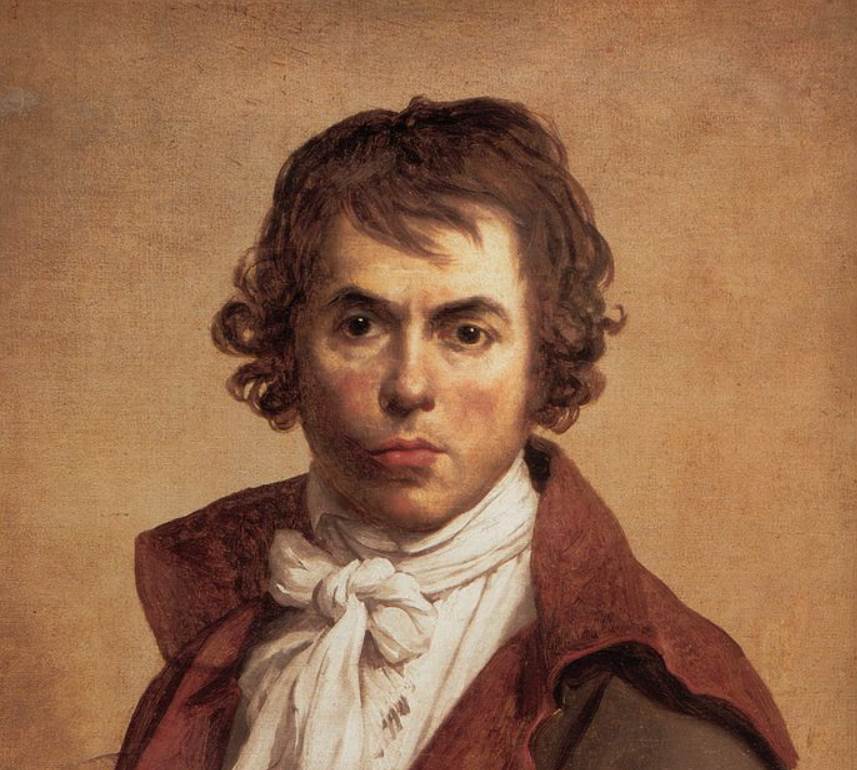

Shortly after Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) won the Grand Prix de Rome in 1774, a prestigious award that allowed him to study in Rome, the French artist departed for Italy.

He studied classical art in the city and it shaped his artistic career. He became the leading Neoclassical artist of his time and produced some of the greatest Neoclassical paintings in history during the 1780s.

In this article, you’ll discover some of the most interesting facts about The Death of Socrates by Jacques-Louis David, one of the artist’s most famous masterpieces.

1. It was completed just before the start of the French Revolution

Something was brewing in France during the 1780s, a period of social unrest that culminated in one of the most important periods in European history.

The French Revolution started in 1789 and resulted in the toppling of the monarchy. As the King and his Queen were abdicated and executed, the frivolous Rococo artworks that were produced by the court painters were replaced with serious and austere Neoclassical paintings.

Jacques-Louis David was at the center of this transition and became politically active during the Revolution as he joined the revolutionaries in their quest.

He was always somewhat of a troubling figure and not the most enjoyable person to hang out with. He was born into a rich family and a facial tumor that impeached his speech. He was, however, determined to become a famous artist, and that’s what happened.

His interest in classical antiquity was strengthened in Rome and he produced multiple works with classical subjects during the 1780s. He completed The Death of Socrates in 1787.

2. It depicts the story of the execution of an ancient Greek philosopher

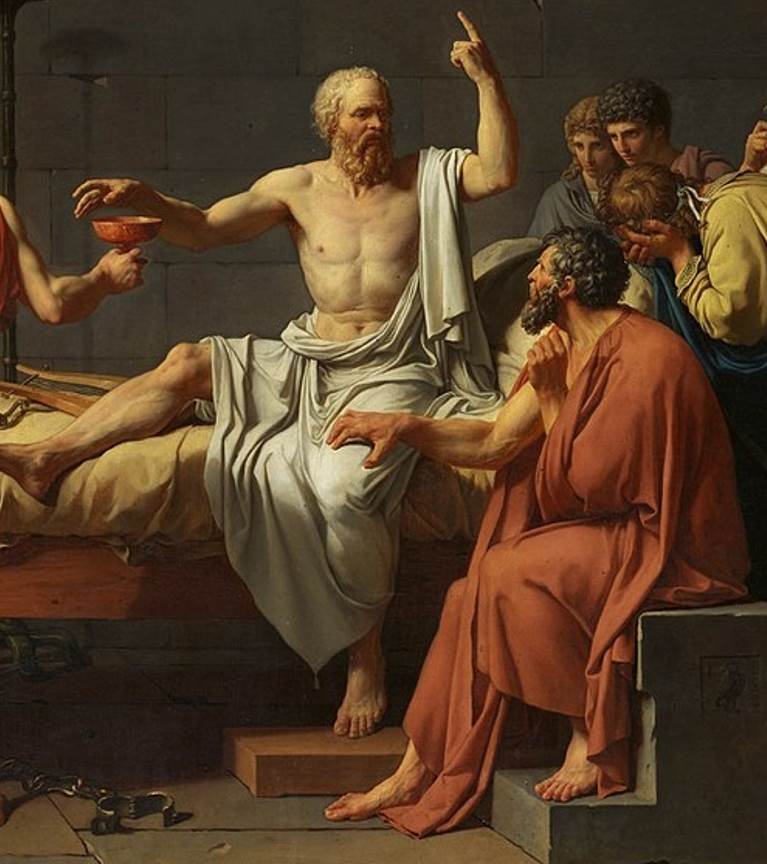

The Death of Socrates is, as the name of the painting implies, a work that depicts the final moments of the great Greek philosopher Socrates (469-399 B.C.).

He was convicted of two things, impiety against the Pantheon of Athens, his native city, and corrupting the youth of that city.

The main argument of the accusers was that they believed that he introduced new deities to the people. This crime was considered to be enough to sentence him to death by poisoning.

The painting depicts the moment when Socrates is being handed the cup of poison. His followers are anxiously looking on as the philosopher uses his ultimate moments to deliver a final speech.

3. The painting doesn’t depict the scene as it was told by Plato

Plato was one of Socrates’ followers and became one of the greatest philosophers in history himself. He is the one who gave a detailed overview of Socrates’ final moments in 4 different works.

The painting was based on Plato’s “Phaedo.” The other works in which he explains what happened are called “Euthyphro,” “Apology,” and “Crito.”

Socrates died in the year 399 B.C. This means that Plato was still a young man at the time because was born in the 420s B.C.

David depicted Plato as an old man who is sitting at the end of the bed on which Socrates is sitting. This is just one of many liberties that David took when he produced this work.

Another striking misrepresentation of the story is the depiction of the distressed Apollodorus. He is the man behind Plato who is facing the wall. Plato’s description mentioned that he was sent away by Socrates for being too emotional at the time.

4. The gloomy color scheme might be a response to earlier criticism

The setting of the painting is a dark room and this is reflected in the overall dark composition. The bright elements in the painting were used to emphasize the emotions in the room.

David completed his most famous work “Oath of the Horatii,” in 1784 and received quite some criticism for his choice of color in this work. Critics deemed the colors to be way too bright for such a dim subject.

He probably adjusted his use of color in The Death of Socrates as a response to this earlier criticism. After all, the subject matter of this painting is equally dim, if not more.

5. David added two signatures to the work and they have a deeper meaning

Jacques-Louis David usually didn’t sign his work at random. It usually had a symbolic meaning, and his signatures in this painting are some of the best examples of this notion.

Yes, he added his signature twice:

- His initials below Plato – A reference to the fact that the story was told by Plato.

- His full signature below Crito – A hint that the artist associates himself with this character.

Crito is the man sitting next to Socrates holding on to his thigh. He clearly shows both a sense of compassion but also uses these final moments to listen to his teacher’s words.

6. several versions of this subject predate David’s painting

David wasn’t the first artist in history to paint the story about the execution of Socrates. Several artists had done so before him, including 2 great examples in the 18th century.

Remarkably, both paintings depict The Death of Socrates in other stages of the event. David’s work shows Socrates before he even touched the cup of poison.

Jacques-Philip-Joseph de Saint-Quentin’s version was completed in 1762 and depicts Socrates shortly after he drank the poison.

This painting is part of the collection of the Beaux-Arts de Paris, a prestigious art school in Paris.

Giambettino Cignaroli’s version of the subject was completed at an unknown date in the first half of the 18th century and depicts Socrates after he already passed away.

This painting is part of the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, Hungary.

7. How big is The Death of Socrates by Jacques-Louis David?

This painting is far from being the largest painting ever produced by David. His Coronation of Napoleon has dimensions of 6.21 × 9.79 meters (20 feet 4 inches × 32 feet 1 inch) which is on a completely different level than this work.

The Death of Socrates by Jacques-Louis David is an oil on canvas painting that has dimensions of 129.5 × 196.2 centimeters (51 × 77.2 inches).

8. Where is the painting located today?

The painting was exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1787 and again at the Paris Salon in 1791. It changed hands multiple times throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

It was eventually purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 1931 and is still part of the collection of the MET today.