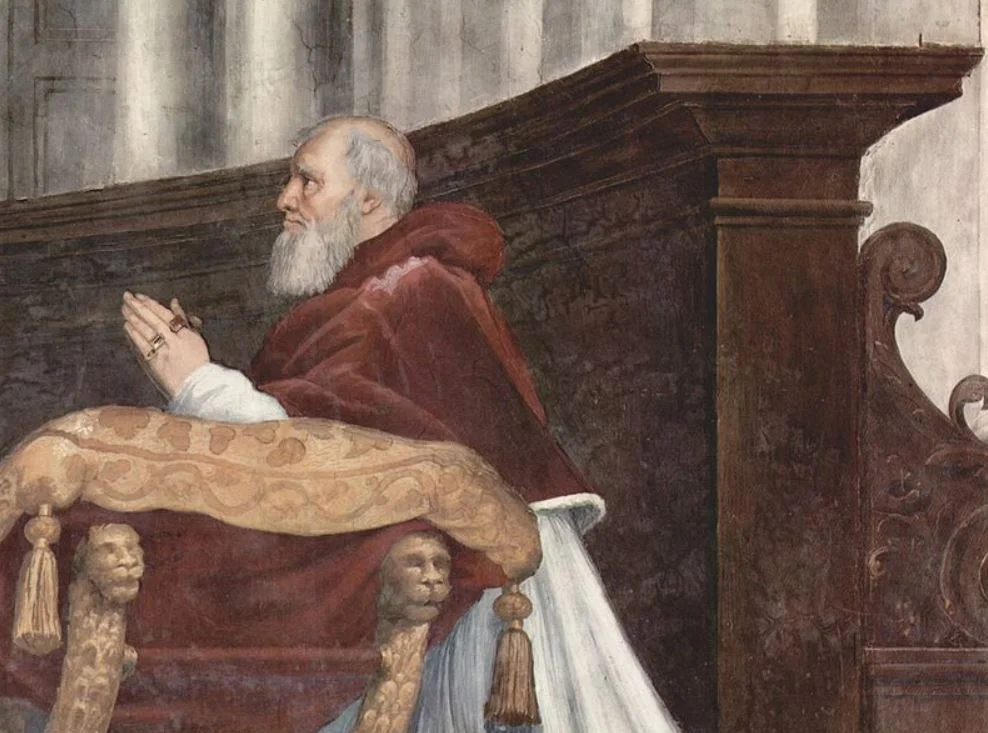

One of the greatest patrons of the arts in the early 16th century was a man named “Giuliano della Rovere” (1443- 1513), better known as Pope Julius II.

He named himself after Julius Caesar and is widely considered to be equally influential in terms of the arts and politics during the High Renaissance. He founded the Vatican Museums and commissioned the reconstruction of St. Peter’s Basilica.

At the same time, he commissioned countless works of art from some of the most famous Renaissance artists in history, including Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Raphael, to name just a few.

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbina (1483-1520) was ordered to paint the portrait of this intriguing figure in world history in the latter years of his life. Let’s take a closer look at some of the most interesting facts about the Portrait of Pope Julius II by Raphael.

It was completed just a few years before the Pope’s death

Raphael was already a renowned artist when he arrived in Rome in the year 1508. This is emphasized by the fact that he was invited to the city by Pope Julius II himself, probably at the request of Donato Bramante.

The next couple of years he worked on the private library of the Pope, now referred to as the “Raphael Rooms.” These apartments in the Vatican Palace are perhaps his most famous legacy as it features frescos such as The School of Athens and The Parnassus.

He received the commission to paint the Pope’s portrait in the year 1511 and completed it the year after in 1512. It’s far from being his largest work as the painting has dimensions of 108 × 80.7 centimeters (43 × 31.8 inches).

It was part of a double commission completed by Raphael

Perhaps one of the most interesting facts about the Portrait of Pope Julius II is that the Pope commissioned his portrait together with another painting. This work is called the “Madonna of Loreto” and was completed in the year 1511.

This painting of about the same size was most probably meant to complement the portrait as it has the same vertical orientation. They were also originally hung together which strengthens this theory.

They aren’t together anymore, though, because the Madonna painting is now located at the Musée Condé inside the Chantilly Castle in France.

The unveiling of the painting was an extremely popular event

The reason why the Pope commissioned these paintings was to decorate the Santa Maria del Popolo church in Rome. This church stands on the northern side of the Piazza del Popolo, one of the most famous squares in Italy’s capital.

This church also stands on the main route north into Rome and both paintings were often hung on its pillars during special occasions such as lavish feasts and holy days.

The paintings were praised almost immediately, and especially the portrait. Hoards of people were lining up to take a look at the magnificent work of art by Raphael the moment it was unveiled, a feast in itself so to speak.

It has been described as a scary painting for a particular reason

There’s a reason why so many people flocked to the Santa Maria del Popolo church in Rome in the year 1512. The portrait of Pope Julius II was so realistic that it almost frightened all the people that stood in front of it.

Granted, the quotes of Giorgio Vasari were written a century later, but he mentioned that “it was painted so lifelike that it appeared as if the man himself was sitting there.” This was enough to freak out the common man in the days before photography.

Apart from being a revolutionary painting in the early 16th century, it also became a great influence for papal portraiture for a long time to come.

The real version wasn’t uncovered until the 1970s

Raphael’s version of 1512 wasn’t the only version of this remarkable painting. it has been copied multiple times, so much that it remained unclear as to where the original version was located until the 1970s.

Now it’s commonly agreed that the original version is located at the National Gallery in London, and the most famous copy in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. The one in Florence was assumed to be the original all this time as well.

This secret was uncovered when an x-ray photograph uncovered a catalog number linking it to the Borghese collection at the Palazzo Borghese, now known as the Galleria Borghese in Rome.

It left this collection in the 1790s and only resurfaced in the Angerstein Collection in London by 1823. The painting that was assumed to be a copy of the original entered the National Gallery in London the following year in 1824.